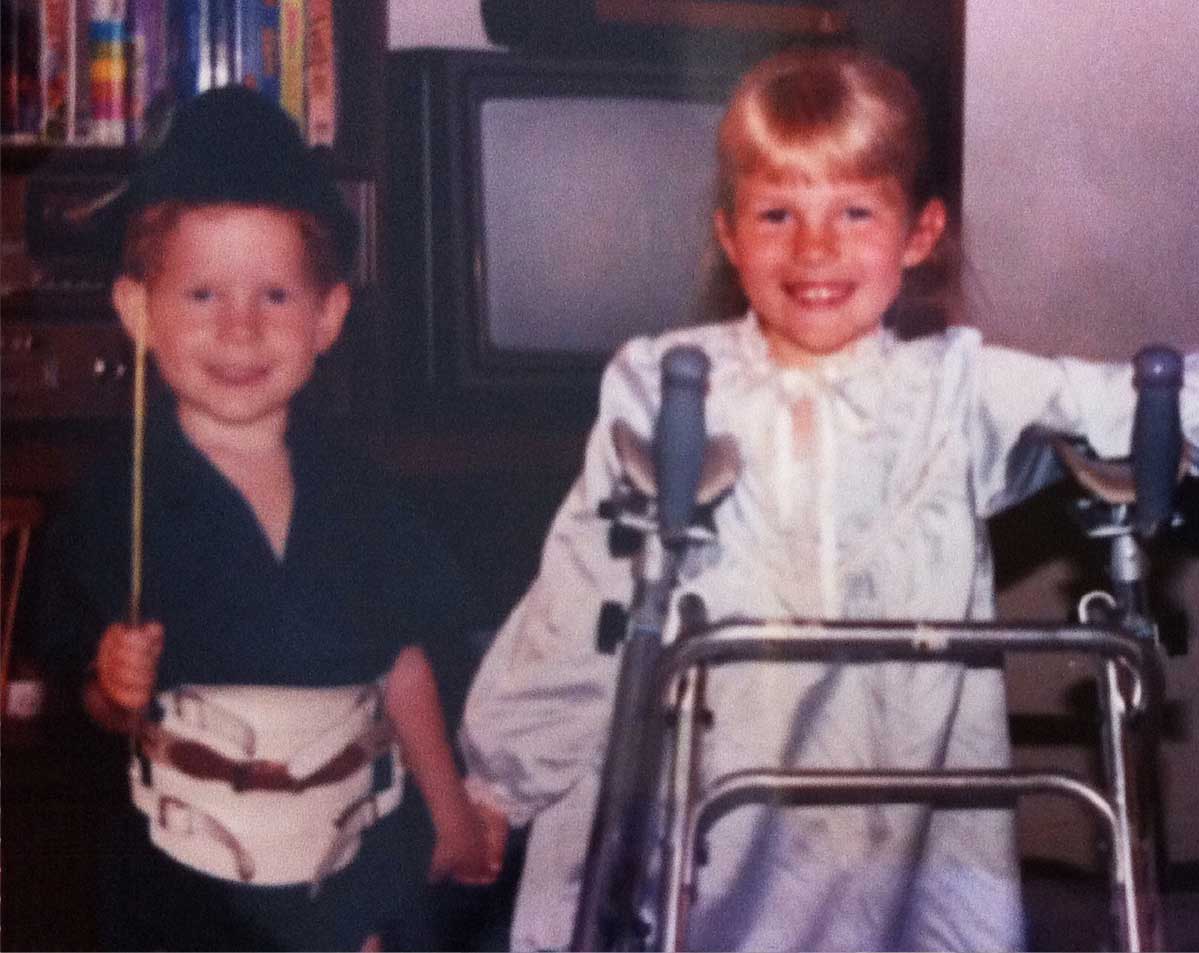

Kevan

Three tips for your next trip

Traveling is a feat for anyone. Now, throw in a disability – throw in caregivers, equipment, terrain issues – and you have another beast altogether.

“Here are three quick tips for putting together your next trip...”

- Intentionality: Traveling is fun, but there is a level of responsibility to keep in mind. As you choose places to go, how to get there and who to go with, be wise. Consider options, challenges and dynamics. Take time hashing it out with your team to develop the best experience possible.

- Simplicity: Some concerns are valid, but travel is not your everyday routine, so don’t treat it that way. What in your everyday routine can look differently for a few days? There will be enough to take in and keep up with while traveling without also worrying about what’s not absolutely necessary.

- Flexibility: For all your planning, keep a loose grip on what it looks like. There will come unexpected change, unforeseen obstacles and blessings alike. Be ready to rethink plans and go with the flow. This is so integral to the adventure experience and I’d hate for you to miss it.

“These three tips are – ironically enough – applicable to any traveler, regardless of 'handicapability.'”

When planning a trip, everyone needs to be intentional, simple and flexible. But when disabilities are involved, the stakes are higher, room for error is slimmer and the need for clarity in these three categories is more paramount. Prepare wisely, consider humbly, develop loosely and, most importantly, have fun!